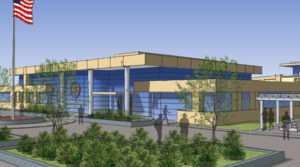

Project to Watch: Why the Utah State Prison Looks Like a College

SALT LAKE CITY — There’s a “term of art” that continues to emerge in corrections facility design circles — “human scale.” The concept was one of the guiding lights for the design of the new Utah State Prison, scheduled to debut in Salt Lake City in 2020.

The college campus–like, 4,000-bed facility will be comprised of small units distributed over two floors, replete with windowed doors that open into a shared day room. The units will be aligned with natural light patterns made available by large windows in a commons area for each bank of units. Locally based GSBS Architects worked with national architecture firm HOK and Miami-based CGL on the design of the project.

The approach echoes the tenets of Utah’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative, which launched in 2015 as a means of reducing inmate numbers and recidivism by “normalizing” the incarceration environment. As a recent article in Utah’s Deseret News put it, the undertaking reflects a “radical theory” in prison design wherein “inmates who live in a normal environment adjust more quickly to normal life upon release,” and it “begins with architecture.”

Coupled with improved occupational and educational programs baked into the overall design, the Utah State Prison could be an exemplar of the future of prison design. The trend is, at least in part, precipitated by a couple of factors emerging across the nation’s prison system.

“Two things are happening — the population is getting older in prisons and you’re dealing with more mental illness,” said Robert Glass, executive vice president and director of planning and design at CGL.

The firm put an emphasis on making “spaces smaller, a little more ‘open’ feeling.” Glass added, “Good colors, good natural light and things, seem to go a long way to help both those populations.”

The design decisions also benefit the staff who have to work with a population that’s shifting from what Glass termed “lighter-custody inmates” who are benefitting from states’ budget-driven early-release programs, to a remaining population of “harder-custody inmates” that are better managed in “smaller unit subdivisions.”

“You try to reduce the numbers of people you’re dealing with,” said Glass. “The mental illness brings in the type of inmate that can be, day-to-day, a little hard to handle. The older inmates, who are getting some dementia, can also be hard to handle, so it’s easier in smaller units to handle them.”

Glass added, “Half the battle with these facilities over the years is having staff have a real nice place to come to work. They’re ‘sentenced’ to eight hours a day there, everyday, too.”

Bringing more design-savvy features to the inmate experience also facilitates rehabilitation, said Glass, whose firm is seeing some of the fruits of their labor realized in a recently completed Southern California facility.

“One of the best ones right now is the Las Colinas Detention and Reentry Facility in San Diego,” said Glass, whose team was instrumental in its conception. “They’re doing a remarkable job with the re-entry programs there. That’s a really open design; it has palm trees inside of it, grassy areas, all sorts of things. I think it’s actually doing two things — the inmates are more successful and I think the staff feels a lot better about working there.”

Throughout these projects, Glass said his firm endeavors to maintain a sense of proportion with the environmental needs of the inmates.

“Really, what we’re trying to do, is keep them low scale. In the mental health facilities, we’re trying to keep them all one level, not even an upper mezzanine level like so many facilities have,” said Glass, who emphasized that these are normal-scale buildings similar to that of a housing development. “We’re also trying to get more space between them now so that there aren’t tight, narrow corridors or fenced walkways.”

Glass said that there has been little critical blowback for the contemporary design approach. He said that critics, if there are any, are usually more concerned with the cost of managing the inmates.

“The critical blowbacks are just on the cost to run these things nowadays. The cost to incarcerate the inmates is about the same as the cost to go to college now,” said Glass about the annual expenditures incurred by counties and states. “That’s the push and the impetus now — to get these facilities working better so that people don’t return to prison.”