Prison Populations to Diverge Sharply in Coming Years

Amidst increasingly clamorous discussions globally about the efficacy and value of the modern prison, statistics are showing more and more that countries worldwide are falling in two separate categories. One, which includes most of the developed economies of Europe and East Asia, is witnessing the waning of the traditional prison through historically low incarceration rates that are expected to decline further over the coming years. The other, which primarily includes emerging economies from across the world, is experiencing pressures to increase prison construction on the back of high and growing incarceration rates that are taxing existing prison infrastructure and will require future investments to prevent conditions from deteriorating past the point of no return.

Moving Away from Prisons

In many developed economies, longer-term economic forces like sustained low growth and slashed national budgets have collided with improved demographic indicators like ever-shrinking crime rates to cause governments to have a supply and demand rationale for restructuring the prison system. Many countries have determined that the cheapest and most effective way to deter crime is through prevention, rehabilitation and training, as opposed to strict incarceration.

As a result of these factors, the inmate population throughout the developed world has seen steady declines over time. From 2005 to 2015, the number of inmates decreased in most countries in Europe (such as in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Denmark and Poland) and developed Asia (Japan, South Korea and Taiwan). The U.S. saw only very slight growth over that period as well.

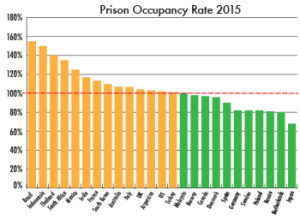

Not surprisingly, most of the countries with sustained, long-term declines in prison population have seen a decline of their prison occupancy rate (the ratio of prisoners per available living space). Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Poland all have an occupancy rate of below 85 percent, a rate that places downward pressure on prison closures and consolidations. This process has already begun in Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden.

And this trend has the potential to build on itself, as governments continue to reform the aims and structures of their prison systems. Already, many prisons in Europe are focused primarily on the reintroduction of criminals back into society, and so prisons have been arranged based on rehabilitative rather than punitive goals, with a higher budget place on training, counseling and job placement activities. As a result, these countries have much lower rates of recidivism than countries like the U.S. (or developing economies), which have much more punitive incarceration models. As this continues, expect further shrinkage of the prison sector in these economies.

Emerging Economies

The feedback loop for many developed countries that has led to positive results over time is reversed for many emerging economies. These markets are witnessing the continuation of persistently high long-term crime rates combined with recent economic slowdowns, causing significant strain on already weak prison systems. With few options to reform these systems, prisons in these markets will continue to be overcrowded, violent and ineffective in alleviating crime.

Of the 30 largest global economies, only a handful saw growth of more than 2 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in prison population from 2005 to 2015; this handful overwhelmingly came from emerging economies (including Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam). At the same time, these markets did not correspondingly increase the number of prisons or expand existing prisoner space.

As a result, the occupancy rate for many emerging economies has reached dangerously unsustainable rates. Brazil, the United Arab Emirates, Mexico, Indonesia, South Africa, Thailand and India all have occupancy rates above 120 percent of licensed prison capacity, with Brazil reaching an incredible 165 percent in 2015. This has a number of deleterious consequences such as increasing violence, malnutrition and criminality within these prisons, but more significant might be the long-term ramifications of hardening an inmate underclass that has limited abilities or options to reintegrate into society.

Conditions have gotten so bad in many of these countries that the only true way out in the near term is through wholesale decriminalization or renewed commitment to the type of infrastructural investment needed just to stabilize their prison systems. For a variety of cultural, political and economic factors, the former solution is not terribly likely in any of these countries, so these increasingly hamstrung governments will have tough choices to make in the coming years about how best to expand these systems before outright collapse.

By Matthew Oster, institutional channels analyst for Euromonitor International, based in London.

* This article was originally published in Correctional News’ Sept/Oct issue.