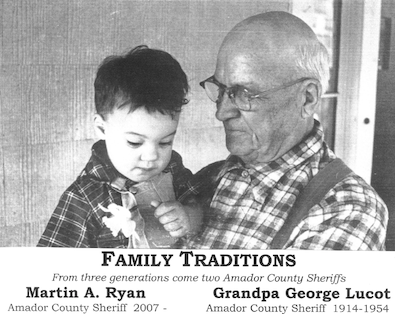

First Families of Corrections: Sheriff Martin A. Ryan

Martin Ryan gently thumbs through a journal and scrapbook of sepia-toned photos his grandfather, George Lucot, kept when he was sheriff of Amador County — a rowdy, Gold Rush-era mining region carved out of California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains with frontier justice.

Martin Ryan gently thumbs through a journal and scrapbook of sepia-toned photos his grandfather, George Lucot, kept when he was sheriff of Amador County — a rowdy, Gold Rush-era mining region carved out of California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains with frontier justice.

In 1914, just four days into his new role, George Washington Lucot was called to a domestic hostage situation. A man had barricaded himself and his wife inside their home and was threatening to shoot her. Lucot, arriving in a buggy with a borrowed gun, tried to calm the man. He responded by shooting at the new sheriff, nicking his cheek with the bullet. Lucot returned fire and killed the man.

“How’s that for a first week on the job?” says Ryan, the current sheriff, who represents the fourth generation of his family on the front lines of law enforcement in Amador County. His great-grandfather, Eugene Lucot, had been a constable (1888-1891), and his father, Martin Henry Ryan Sr., served as a deputy sheriff in the 1950s before becoming a Superior Court judge.

Despite his harrowing start as a peace officer, George Lucot went on to wear the badge for 40 years until retiring in 1977, setting a record for the longest continuous term in the country and earning tributes in the detective magazines of the era.

“Lucot was quite a figure of a man, a big guy standing taller than six feet, a genuine ‘John Wayne’ type,” recalls Don Howard, 77, also a deputy who became a Superior Court judge. “Lucot made it a point to have lunch in a different place every day, and he knew every single thing that went on in the county. He could knock heads with the rough guys and keep order when he had to, but he was kind to kids and was a skilled politician, too. Sharp. Tough but fair.”

By all accounts, Lucot was the sort of larger-than-life presence Amador County needed at the time. The rugged terrain presented all of the mythologized, hair-trigger challenges of the Old West, where strong-backed fortune-seekers craved serious rest and relaxation after a hard day’s work. Miners would go on strike and carouse with construction crews of ex-cons at more than a dozen saloons on the main street. Gambling was legal until the early 1950s. And the county was the last hold-out in California to outlaw prostitution in 1956.

“In other words,” Howard says, “the place was wide open.”

Adds Ryan, “How my grandfather handled fights shows you what a different time it was. He would break them up by challenging and fighting the leader of the rabble-rousers himself.”

Lucot also kept the peace during the Argonaut Mine disaster, considered the worst in California’s history, when 47 men, mostly recent European immigrants, were trapped and killed in a fire 4,650 feet below ground.

As Amador County quieted down, Ryan Jr. grew up in the house his grandfather built. He planned a more sedate career, however. After earning a history degree from the University of California, Davis, he was in his first year of law school in 1975 when a position for chief investigator opened up in the district attorney’s office.

“I suggested to the D.A. that he hire Martin,” Howard recalls. “He asked me if Martin was even interested in that line of work, and I said, ‘I have no idea, but it’s in his blood, and I’m confident he’d be good at it.’ And sure enough, he took to it like a duck to water, and since then, Martin has proved himself to be the best law enforcement officer I’ve ever known.”

After several years as a chief investigator, Ryan joined the California Department of Justice and was assigned to the Los Angeles Office of the California Bureau of Investigation (CBI). “It’s what the television show ‘The Mentalist’ is based on — very loosely based,” he says.

In 1981, he was transferred to Sacramento, where his first case was the investigation of notorious serial killers Charles Ng and Leonard Lake, who are suspected of murdering between 11 and 25 victims and filming their rape and torture. (Lake committed suicide; Ng is on death row.)

Ryan became one of CBI’s first members of a new Criminal Investigations Response Team (CIRT), specially trained to investigate homicides, serial murders and officer-involved shootings. He steadily advanced up the ranks of the organization, covering the gamut of gangs, corruption, organized crime, sexual predators and domestic terrorism, until he was appointed by the attorney general as the chief of CBI in 1999. He served in that leadership role, as well as national chairman of the Association of State Criminal Investigative Agencies, until retiring in 2005.

Then his old friend, Judge Howard, piped up with more career advice.

“I told him to come back to Amador County and run for sheriff,” Howard says. “It would be a full circle.”

Ryan, who also looms tall in stature and still possesses his grandfather’s badge and gun, is now in the second year of his second term. “I love being engaged in the community I grew up in, running into people I went to kindergarten with,” says Ryan, whose two brothers — George, a lawyer, and Mike, the county treasurer and tax collector — also live nearby. (Grandfather Lucot’s responsibilities as sheriff included tax collection, so Mike is holding up that end of the family banner.)

The next generation, too, is dedicated to public service. Ryan’s son, Joe, works as a deputy sheriff in Placer County, near Lake Tahoe, and his nephew, Casey, is enrolled in the San Diego Law Enforcement Academy.

Much has changed in scenic Amador County since his forebears tangled with brawling miners. Ryan oversees a staff of 100, a $14 billion budget, and a 76-bed jail known among inmates as “one of the nicest county jails in the state,” he says with a laugh. “My grandfather just had one or two deputies. What I do is like running a corporation, with ‘public safety’ as our product, but it is humbling to carry on this family tradition. And so far, I haven’t been shot.”