Increase Reported for Deaths at County Jails

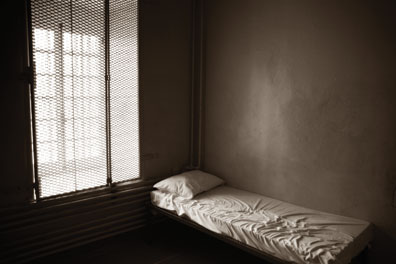

Inmate deaths at county jails in the United States have risen significantly in recent years to a higher percentage per capita than in state and federal correctional facilities.

It can happen in any facility, no matter how tight the security procedures, or how well intentioned the jail’s on-duty medical staff are.

Inmate deaths while in custody are on the rise across the United States, triggering uproar in local communities and a spate of lawsuits against multiple jurisdictions responsible for the safety of inmates in confinement. Of particular concern, according to reports, are county jail facilities, where the bulk of in-custody deaths have occurred in recent months.

In California, the rise has been incremental over the past 30 years, according to documents provided by the California Department of Justice. In a report outlining inmate deaths between 1980 and 2010, deaths of inmates in custody across all types of incarceration rose from 127 in 1980 to 447 in October of 2010 (the most recent numbers available). In 2009, in-custody deaths in the Golden State rose to 694, compared to 608 in 2008, and 730 in 2006.

The DOJ Death in Custody report supports the notion that that majority of deaths occur from natural causes or illnesses — with 281 such situations thus far in 2010, compared to a high of 464 in 2009, and a low of 50 in the years 1980-82.

In Santa Rosa, Calif., officials are still dealing with fallout from three in-custody deaths at the Sonoma County Jail over the past three years — one that occurred in September 2010, another in the fall of 2009, and still another that took place in 2007.

In the September case, a volatile inmate arrested days earlier on a variety of charges — including evading arrest and battery on a deputy — managed to climb to the top railing of a second floor tier in a direct supervision pod and dive headfirst to the floor in an attempt to take his own life. Correctional officials responded and administered aid. The inmate, who was also wanted on Fugitive Warrant from Arizona, was taken to a local hospital where he was pronounced dead.

In the 2009 case, a 44-year-old man was found dead in his cell from an apparent cardiac arrest and could not be revived in spite of efforts of jail and medical personnel. The Sonoma County District Attorney ruled that the sheriff’s office was not at fault in the case.

In the 2007 case, an inmate died of sickle cell anemia after losing 44 lbs in the last week of his life, according to reports. The family of the inmate filed suit against the county, and in October of this year a federal judge ruled that the family could sue because the facts about the case are in dispute.

The trial is slated for January. Named as defendants are former Sonoma County Sheriff Bill Cogbill, who recently retired, and Sutter Medical Center in Santa Rosa, where George had received treatment.

Sonoma County Sheriff officials would not comment on the pending litigation, but Sheriff Capt. Philip Lawrence explained that jail officials follow protocol for inmate healthcare established by the California Medical Association’s Institute for Medical Quality, and that the department had recently been inspected and received a two-year accreditation — the highest available from CMA. He added that the jail had been fully accredited by CMA at the time of the deaths in 2007 and 2009, as are most, if not all, county jails in the state.

California does not have the corner on in-custody inmate deaths. Inmate deaths in Texas have resulted in a call for an examination of healthcare standards in the Lone Star State.

The frequency of deaths of inmates at county jails throughout Texas has led to a call for increased healthcare standards for inmates. A recent article in the Texas Tribune reported on information provided by the Texas Attorney General’s office that illustrated how inmate deaths from illnesses in county jails there rivaled those in state penitentiaries — in spite of the fact that county jails house half as many inmates and they are typically in-custody for far shorter periods.

The report showed that out of 1,500 deaths in law enforcement custody statewide between January 2005 and September 2009, 500 of them occurred in Texas’s 254 county jails.

While some of the 500 deaths occurred as the result of high-intensity pursuits or suicides, or in the course of an arrest where the individual was shot, tased or restrained by officers, 282 of the reported deaths were a result of illness or a condition the prisoner developed before or during incarceration, according to the Tribune report. The various causes of death ranged from heart conditions, cancer, liver and kidney problems, to AIDS, seizure disorders and pneumonia.

“The medical care that [an inmate] gets in the jail is very dependent on the initial screening,” says Michele Deitch, senior lecturer at the LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

“Are you being adequately identified as having certain medical problems or certain mental health problems? It’s only going to be as good as the screening instrument and the diagnostic process and what kind of medical personnel are there assisting in that effort. If the jail is inadequate on that front, you’re going to see some more consequences.”

Deitch says that verifiable standards should be set for the delivery of healthcare to inmates in the jail setting.

“Jails are subject to relatively little oversight,” Deitch said. “They’re not very transparent as far as the public is concerned or policymakers are concerned. The [Texas] Commission on Jail Standards provides a reasonable level of oversight on certain issues but not on this. So I think it would be very important for there to be applicable standards on healthcare and for them to be monitored and for there to be publicly-available reports issued by the Commission on Jail Standards about if the jails are complying with those standards.”

Deitch said that there is a “natural disincentive” for jails to provide such services unless there is a lawsuit pending or if administrators at a jail are thinking they can get away with less than optimal care. She added that jail healthcare is uniquely different from prison healthcare — a factor that could contribute to the inmate fatality problem.

“For one thing, the inmate is coming in from the street,” Deitch said. “You’ve got that sharp break with whatever medical care there was from the outside. So the inmate, for example, might have been on a regular medication on the outside. Maybe he had a heart condition and had to take a certain kind of pills, and didn’t have them on him when he was arrested. He might need them very soon after arrest, but there may not be a protocol to get that medication to him or even for confirming that he is entitled to that kind of medication. It may be a long time before he is appropriately diagnosed and jail medical staff allows him to have anything and it may not be one that continues the medical regime he was on. That’s a concern — that lack of seamless delivery of medical services.”

Deitch added that inmates coming in that have been abusing alcohol or drugs present a potential complication to the delivery of medical care and mental healthcare.

“We know that jail inmates are a particular risk of suicide, particularly in the first 24 hours after arrest,” Deitch said. “So you’ve got mental health concerns that are very, very specific to a jail setting. Also, with regard to medicines, you’ve got inmates, for example, that are on AIDS cocktails.

“If you don’t get the right combinations of medicines in the right intervals, your entire medical regimen could be compromised,” she said. “In effect, even if you were to get out in a few days, it could actually be a death sentence.”