Combatting the Fentanyl Crisis in the Corrections Industry

By Alexander Sappok

Fentanyl has caused more deadly overdoses in recent years than any other opioid, and it has increasingly become a main focus of the fight against drugs. As a result, government officials and leaders in the private sector alike are beginning to see the need to create a unified response to the crisis and work to reduce overdose deaths throughout the world.

Still, many correctional facilities are not equipped to respond effectively, and the influx of fentanyl continues. Today, some jails and prisons are at last finding better ways to detect fentanyl in mailrooms and develop operational procedures for responding to the influx of drugs. It’s time for every facility to take a unified look at these new strategies, take action to stop the flow of drugs, and respond more effectively to this crisis.

The State of the Fentanyl Crisis

Every year, the number of fentanyl overdoses increases and more inmates and correctional officers are in danger of exposure, illness, and death. But how does fentanyl get into jails and prisons in the first place, despite all the safety and security measures these facilities have in place?

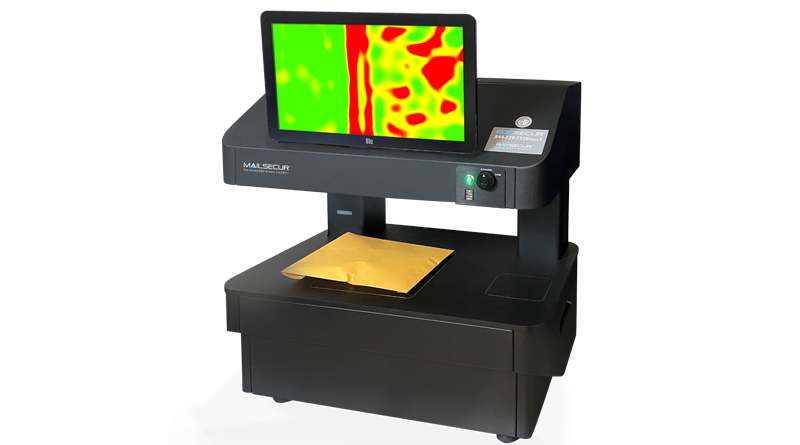

For starters, fentanyl often comes into the U.S. through international postal mail from China, Mexico, and various other countries. Most international mail is X-rayed, yet fentanyl continues to get through since it often comes in small amounts of powder that are undetectable with X-ray scanners. Other methods for detecting fentanyl, like drug-sniffing dogs, are too expensive, may put the dogs at risk, or require too much infrastructure to effectively stop the flow.

Once fentanyl is in the country, the next destination is often the prison mailroom. According to the NIH up to 85% of inmates have an active substance use disorder or were incarcerated for a crime involving drugs, making prisons and jails a prime target for fentanyl sales. Only this September, two corrections officers and five inmates were exposed to fentanyl in a county jail. In another county jail, two corrections officers were exposed to fentanyl in the mailroom and were sent to the hospital as a result.

How Can Prisons Respond?

For prisons and jails to protect staff and inmates from fentanyl exposure and overdoses, they need to step up their protocols and infrastructure to detect and stop fentanyl at the door.

First and foremost, correctional facilities need to develop and align on a standardized response to the crisis, one that can be shared across different locations and across both private and public facilities. Authorities agree that one of the top reasons efforts to keep fentanyl out aren’t always effective is simply the lack of cooperation among various government and private entities.

Given the ever-evolving nature of the problem, increased transparency and the sharing of information and resources is critical, so that facilities can create effective standard operating procedures for scanning mail, quarantining packages and letters that are contaminated or may contain a dangerous substance, and disposing of dangerous substances appropriately.

By keeping internal security and mailroom personnel informed of the best policies other facilities have in place and relying on external support resources where necessary, correctional institutions can begin to pool their resources and information to best address this critical problem.

As part of pooling resources and developing a standard response, prisons can also begin to seek out better education and training options for mailroom staff. Facilities that are under-staffed or lack expertise in certain areas in-house can rely on outside expertise from security experts in corrections, law enforcement and narcotics, and from former military personnel already well-versed in detecting and handling dangerous substances.

Next, corrections leaders can rethink funding and spending on safety and security. In many cases, mailroom personnel may be entry-level or subject to high turnover, with limited training in security processes. Most mailrooms also lack technology screening tools to detect fentanyl and other drugs. Yet at the same time, many correctional facilities often have a large budget dedicated to physical security, facility operations, or even inmate welfare funds. Correctional facilities should consider shifting resources more equitably across their various security threats, including mail-scanning technology in addition to staff education and training on mail security topics.

No industry has all the answers, but many have access to the experience and technology that can stop fentanyl from getting through. Decision makers in correctional facilities must prioritize their resources to address the source of the problem by keeping fentanyl and other dangerous drugs from entering their facilities while ensuring staff safety and allowing safe mail to be delivered to the intended recipient unimpeded.

Alexander Sappok, PhD, serves as CEO at RaySecur.